The “normal” classroom is not one where every 8-year-old is meeting 8-year-old developmental markers, or where every 15 year old has the same reading level. This is reality.

When you have an infant, you’re looking for signs that they’re developing normally at the appropriate, expected pace.

You’re watching for the first smile, first crawl, first word, first tooth, first bites of food, first step. You’re trying to see if every day they’re moving closer towards the development you expect. There are changes week to week, sometimes day to day, certainly year to year as they grow up.

As a teacher, we also look for signs of “normal” development. We look for kindergarteners that skip and play showing gross motor skills and controlled fine motor skills of handwriting grips. We assess young students for phonemic awareness and if they can rhyme words and segment and blend sounds. Anyone who has studied early childhood development knows that there are milestones we want to meet.

But as the years get further away from infancy and clear-cut 6 months vs 9-month goalposts, it becomes difficult to say what this 10 year old child *should* be doing. What about when an entire class of 10 year olds seems to be “not normal” or “not on pace”? They seem immature or just “all over the place” as I’ve heard so many teachers describe groups of students. How do you manage a classroom where “average” feels like it’s lost meaning?

Principal Gerry Brooks has a popular video on Facebook, Paradigm of Education, that describes how many students in a “normal” classroom will be economically disadvantaged, below grade level expectations, and have mental health difficulties or trauma. As he says in his video, “This is reality.”

Differentiation is not something that is nice to do as a teacher; it is necessary in order to meet students where they are and support each student in growth, not just the 5 per class that are showing textbook development. These gaps often grow as students get older even though “closing the gap” is a goal of almost every school district.

My 2nd-grade classroom can span K-3rd grade reading levels while my 6th-grade classroom would usually span 2nd-8th grade. Each group of students is different so each class I’ve taught has had different collective strengths, needs, and concerns, but I’ve never had a class where everyone was just moving along at the same pace all year, came in at the same levels, had the same support at home, had the same languages spoken at home, had the same needs from me, or anything else the same.

People are different, and that shows up in our classrooms now more than any other time in US history due to the fact that now is the time we have made education the most open and accessible to more of the population. This is a good thing! This is not an easy thing. And in order to keep working towards educational equity, we need to create systems that work to meet these students when their needs and abilities feel scattered.

Part One: Differentiate the way you ASSESS

We often think about planning when it comes to differentiation, but I want to start with thinking about how to differentiate assessment. I think teachers often get frustrated because as much as we are told to differentiate in the classroom, all students have to take a standardized assessment anyway – either at the district, state, or even nationwide level. After all, isn’t it only fair if everyone gets the same test? I don’t think it is actually, particularly for English Learners.

Through IEPs, students receive accommodations for standardized testing such as extended time, flexible schedule, read aloud, dictate to a scribe, and so on. Often, ELLs (English language learners) are not provided the same types of differentiation in assessment. It’s often simply expected that they will perform badly because they are not fluent in the language.

While you may not have control over a district or state assessment, why not change classroom assessments so that you can actually see what they know related to the curriculum?

I’ve heard some teachers respond, “They won’t get that on the district/state test, so it doesn’t matter.” I think it matters a great deal.

A student who scores highly on a test with a few modifications or accommodations is going to feel awesome about their ability to learn and is going to keep working towards it. If they still fail that state-level test, at that point, the student will know it was the test and not them that is a failure because they do know the material and they have demonstrated acquisition of knowledge and skills in the classroom setting.

In addition to that, this differentiation of assessment could have a huge impact on their classroom grades. For many classes, our job is to assess their content area knowledge, not their spelling or reading comprehension, so you can assess what you need to assess and let go of what might be holding a student back from demonstrating that knowledge. This makes a huge difference to me, and I’ve seen how students feel empowered by getting good grades on assessments with accommodations.

1. Read Aloud

I think the easiest way to differentiate is to just read aloud a test to a select group of students. Also, if you like, you can read aloud a multiple-choice test to all students as a class, allowing some to go at their own pace if they like and others to follow along with you. You could have students raise their hand and you go to them individually or have them come to you with a question.

A certain feeling of safety needs to be built up between teacher and student, especially with older children, for this to work in a way to truly provide the accommodation, but all it takes is a couple of brave kids to ask how to read a vocabulary word and soon everyone will feel that sense that they are allowed to ask. Even if this doesn’t go that well right away on the first formal assessment, try it again. They may feel more comfortable with you later.

2. Simplistic Language

One fairly easy way to differentiate assessments is to just use a version of the test with more simplistic language. Read through your assessment and see if you can make any words a little more basic, easier to read, less nuanced.

I understand your hesitation if you’re an English teacher, but you can likely make directions a little simpler. Removing a step, reducing or condensing the language, spreading out questions, and adding more space to a page are all ways to differentiate a test that doesn’t require a huge amount of effort on your part.

If you struggle with reading, sometimes too much text on a page is just overwhelming. Is there a way you can break it up? Physically add more spaces between questions? Use a table to make the directions for what to do more obvious? Double-space and give a window cut out to read a line or paragraph at a time?

3. Adding Images

This was my favorite way to differentiate for science assessments. All I did to my test was add pictures. For instance, on a test about which cloud goes with which weather, I added a picture of a cirrus cloud. Then, I added a picture of a cumulus cloud for the next question.

Why might I “give it away”? Well, if you’re an English learner, maybe cirrus and cumulus are difficult for you to differentiate. Or if you have dyslexia, maybe those words keep getting flipped in your mind and it’s frustrating.

If you have a photograph to anchor you, you’re more confident to answer the question. It’s not that you didn’t know which type of weather was associated with which cloud, it’s that you’re constantly second-guessing yourself because of a vocabulary word. If the goal is to predict weather based on cloud formations, I think an image is a great way to measure that skill and standard.

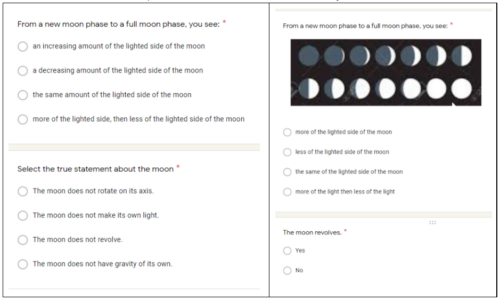

These are screenshots of Google Forms quizzes I have given. The standards assessed on the left and right are the same but the presentation of the information has been adjusted to accommodate students.

4. Verbal response

Tracking can be difficult for some students with disabilities. I have watched students circle “D” on #9 right after reading #8 when they meant to mark that question. Then, they get confused as to what they read and what they’re marking and have to start all over again.

Sometimes it can be more efficient to accept a verbal response to a question if a student is losing track of what they are reading. I often combine this with a read-aloud accommodation. The fascinating thing I’ve noticed is often if I’m reading a multiple-choice test, sometimes students will tell me the answer before I’ve even read the choices because they know the material!

The problem is that when they go to take the test on paper, it’s so taxing they miss half the questions! This truly has happened to me as a teacher, and it’s convinced me that I should accept verbal responses.

5. Dictate to a scribe

Unless it is a writing assessment, if a student significantly struggles with writing and spelling, I will allow them to talk to me, and I will write their words on paper for them. This is an accommodation on many IEPs so sometimes it’s mandated that I do this, but sometimes it’s not. I think you would know as a teacher who would truly benefit from this and need it.

6. Allow for drawing and make it more accessible to all

Consider how you could make an assessment a little bit more equitable. Instead of asking students to list 3 reasons why they would prefer to explore a Pueblo, Powhatan, or Lakota home, have them draw one of those homes and label the 3 things that are important to the tribe they chose. You are getting the same information but you’ve allowed students to show what they know in a way that doesn’t require a whole paragraph of writing.

If you don’t have to have an essay as a response, consider how you might incorporate some form of drawing or expression. Perhaps you can embed matching or sorting or putting images in sequence instead of words. Is there simply a way you can make the assessment more accessible to everyone. Many teachers typically provide word banks to support spelling and writing, but perhaps there’s a way to assess entirely differently (although word banks can be great!)

When I taught 6th grade, kids knew if they were getting a test with pictures vs. a test without. About halfway through the year, they would ask me if they could take the “regular” test. I always said yes, but I told them to take the one with pictures first. Then, they would feel more confident going into the other test. I told them I would take the better score of the two tests. I think that’s totally fair since they were doing more work.

This often meant these kids were some of the last to finish because they took it twice, but they worked so hard and immediately wanted to know how they did. This is the type of motivation I want to see related to assessments. They were looking for growth and they were seeking a personal challenge.

It wasn’t that they were obsessed with getting a perfect score; they were thrilled to see improvement over time. I cannot express what a joy it was to see students thrive like that – it’s exactly what we study in education classes about the zone of proximal development and moving a student towards their goal.

Part Two: Differentiate the way you TEACH

Now let’s consider what people usually mean by differentiation, that is, in terms of lesson planning and creating different materials or tasks for different students. For me, the easiest way to differentiate my planning was to group students into small groups and teach a majority of the content that way.

Here are some ways to differentiate between small groups. You can group students flexibly and change as often as needed. I often keep groups the same for an entire unit or more simply to help students foster relationships and have a “go to” person if they get lost or need support.

1. Change the content in small groups

Teach what students need based on pre-assessments or reteach based on any current assessments. I think this is the default for many when they consider the word “differentiation.”

I use quizzes and tests to group students by what they missed. Then, we can go over mistakes together and each group has similar needs. Then, no one in the class feels like their time is wasted because I’m only going over the content they missed on an assessment. If you group a quiz by standard or skill, this sets you up for that.

For any students who made very few mistakes, you can just group them together, ask if they have any questions, then do an enrichment task. You do not even have to do this as a small group station. You can also allow students to work on an independent task then call over students by part of the quiz/test so that everyone is working on something and you can see some kids for most of the time while others you might not see at all.

2. Change the pace

Teach the same content slower or faster to different groups. You can provide more time to take notes, ask questions, or process information. You could do more or fewer problems with different groups of students and adjust your pace in response to a smaller group. You could repeat the same problem or task to solidify the learning or backpedal as needed.

The goal is to do the same basic task with all students. If you’re working through some sort of designated program and they’re understanding one “level,” you can skip ahead and move onto the next part without worrying if you’re leaving someone behind.

3. Change the level of the work (but keep the content the same)

- Choose multiple levels of the same text or select texts all on the same topic or within the same genre that are at different levels. You can find leveled texts through a platform like Newsela and many reading sites. Guided Reading typically follows this structure where you’re doing a similar lesson but using a different text that is at the instructional level of students.

- You can choose different leveled problems such as 2 digit no regrouping, 2 digit with regrouping, 3 digit addition without regrouping or 1 step vs. 2 step problems. You can also change the numbers in word problems. You can do the same word problem with students but one group uses simpler numbers while another does larger numbers.

- You change your expectations slightly so that one group is expected to write 3 sentences while another group writes 6 sentences. Of course, students can always do more and may surprise you, but the expectation is adjusted to be an attainable goal that will result in a feeling of success.

4. Add a modification

You can offer some students manipulatives while others are not required to use them but might still have them in view. You can draw a picture for some students to follow along. You can read aloud a passage with some students while with another group you let them read it on their own. You can pre-teach a few vocabulary words before a passage only with one group that might not have the background knowledge yet.

Pull up some google images of “rainforest” before reading the book to prep students who might not have had that exposure and can’t predict anything in the story. That type of modification can be 100% responsive and in the moment; it’s not something you have to plan. I’ve often pulled up images on my computer to show students in guided reading when I realized they couldn’t make the connection or prediction I thought they would be able to make.

Whatever you choose to do to differentiate for small groups I recommend that you:

Use data: It can help to group questions on a quiz/test by standard or skill so that you can easily group students by the part they missed or the part they missed that is most essential to moving forward. You can use a standardized assessment or reading diagnostic to prioritize which strategy to teach students.

Stay flexible: Groups are not meant to be static. My favorite way to differentiate is actually purely by pace. Something that could be taught whole group goes ten times better teaching it small group because I can be more efficient and responsive.

Some might argue this is a waste of time because I could just teach it whole group in ¼ of the time. Time is not the only factor here; students often understand better in small group and require less reteaching over time.

In small group, I can catch misconceptions in real-time, reteach as I need to, and provide a more challenging problem when I see they have it. It also allows me to see who is falling behind or moving ahead in a small group so that I can rearrange the next week fairly easily.

There are many benefits to consistency in groups and I enjoy heterogeneous small groups sometimes, too, just to allow kids to work with different people. Groups are meant to be intentionally created, but you can change your intent.

5. Differentiate whole-class lessons

Often teachers rely on small group instruction to be the time for differentiation, but consider these possibilities for how to differentiate a whole class lesson:

- Use 2 sample texts that are different reading levels so that you’re using 2 different mentor texts to teach the same point.

- Allow students to choose which word problem to solve and share out loud.

- Read aloud the passage or allow students to read at their own pace.

- Provide visual support.

- Have supportive charts such as sentence frames, vocabulary words, familiar diagrams or procedures.

- Use partnerships for students to talk to one another; you can also use triads to support students – one lower-level English learner with more verbal students so they can hear the language modeled.

- Make use of proficient dual language speakers (for example they can repeat directions in Spanish and English).

- Have different types of paper available that are borrowed from primary levels of school – some with a space for pictures to draw and some with only lines.

- Use captioning/subtitles for videos you play in class.

Part Three: PLAN with a structure for differentiation in mind

1. Differentiate independent work

When students are doing independent work, provide work that is meaningful for students working on primary or foundational skills. This might mean an online program that is set at the right level. But more often, this will mean just-right books for reading, math practice that has multiple levels of difficulty so that students can do different levels of work to meet their needs. Or offering listening to speaking as an alternative to reading, etc.

In a personal blog post, “How I teach reading to a class that spans 7+ grade levels”, I shared how I taught reading to my 6th graders, where I give some recommendations for how to keep work age appropriate even when students are working on basic skills.

2. Provide choices to allow for self-differentiation

When I was in college, we learned about differentiation from the model of Carol Ann Tomlinson who explained how you could differentiate process, product, and content (see page 288 for a simplified diagram). Often I heard this explained in a way that fostered self-selected differentiation.

For example, as a student, I could choose to make a trifold or a PowerPoint (product). I could choose to research Ancient Greek Gods or the history of the Olympics (content). I could choose to read or watch a video to learn information (process). These types of choices are incredibly valuable in the classroom.

While this was often discussed within the context of gifted students, all students benefit from choice. Choices often elicit buy-in from students and provide interesting variety. While I can assign different levels of text to different students based on assessments of reading level or assign projects and tasks to students based on my belief in their ability to handle specific tasks, students will often self-select very accurately to their level of challenge.

I would even say that often students can self-select more accurately than we can assign for them. Abilities are flexible. I have had the experience over and over again of seeing a struggling reader devour a novel that they loved and understand it when they couldn’t pass a grade level comprehension test. Or hear a student use advanced vocabulary describing sea turtles and climate change without being able to write 1 sentence about it.

In one episode of “The Office,” Kevin makes calculations regarding pie even though he cannot do any math computations outside of the pie scenario (despite being one of the accountants). While this is extreme because it’s a comedy show, the same thing can be seen on a small scale when I make the word problem in math about buying soccer equipment instead of buying apples.

Motivation can strengthen abilities and make weaknesses practically dissipate. This is not always true, of course, but it happens often enough that teachers know how valuable motivation is! This type of differentiation based on choice and pleasure is not something that we can manage all the time, but we can plan ahead for it in many situations. Even offering 2 choices of which article to read or which worksheet to do can be powerful.

You might be thinking, “With so much choice and so many accommodations, what is even the same? What is holding a classroom together? What needs to be the same for all students?

I’ve heard a teacher say before, “My job is to teach ____ grade level math. That’s what I’ve been assigned to teach.”

You might assume this teacher did not differentiate or reteach concepts to students; however, I happen to know that this particular teacher had a huge heart for struggling students and worked to get them to understand grade-level material by filling in gaps. This statement was made in response to the frustrations of a parent who wanted this teacher to teach the next grade level of math curriculum to their child.

Even though I empathized with this teacher’s frustration, I thought the statement was interesting and still slightly problematic. Is that what I’m hired to do? Teach 5th grade math or Biology or AP Literature or 2nd grade?

Someone might counter, “You were hired to teach these students.” I want to agree with that, but is that all? On some level, you ARE hired to teach Biology. You are expected to teach a set of curriculum. That is where the struggle comes in for us as teachers. We want to abandon the curriculum sometimes and just teach what students need and sometimes we want to teach a unit on dinosaurs because it’s fun! Standards cannot be completely abandoned or we really are going to be accused of not doing our jobs, even if we think we’re doing what’s best for students. So what can you do?

3. Focus on essential standards for equity

Not all standards are created equal. Understanding the differences between the author’s purposes to entertain, inform, and persuade is not as important as being able to read fluently. Knowing the names of geometric shapes is not as important as fluently adding and subtracting within 20. Being able to identify personification is not as important as being able to write a paragraph with a topic sentence.

When you look at the standards that you are supposed to teach, think about which ones students really need to master for their success in the long term – not for a test, not for this month – but in order to move on to the next grade level with a foundation.

Which standards will have the best use over time? It is our responsibility to teach both students and standards, but which standards we prioritize is our choice as educators. This is an important discussion to have with a grade-level team of teachers and even through vertical articulation by talking to future grade-level teachers.

What is vital to the student’s success? Can you and a team of teachers select a handful of standards for each unit or content area that are MUSTS? These are the ones you’re going to relentlessly reteach throughout the year whether or not the unit has passed, whether or not you’ve “covered” it in the time allotted. And if students are missing foundational skills needed to reach these standards, those are the ones you’re going to go back to in order to get them to a point where you can teach the grade-level standards.

You are not going to do this for every standard you’re expected to cover; you’re going to select and prioritize with the idea that when a student leaves your class, they will be able to do these things. In fact, for many standards, go ahead and “cover” them; do a quick lesson and move on. Everything we teach is “good to know” and “useful” but not everything is vital.

4. Use low floor, high ceiling tasks

For whole group lessons, choose tasks that are open-ended. Use thinking routines such as “See Think Wonder” where students can share what they notice and wonder about an image or from a video. This piques the interest of the class and allows for self-differentiation. Students will share answers that are at their own level; meanwhile, all answers are valid.

If you’re having students share ideas that could be correct or incorrect in your context, ask “What makes you say that?” indiscriminately so you can gather information about how students are thinking without judgment. If you scroll to #8 in this article on 8 Ways to Stay Ahead in Lesson Planning, you’ll see lots of ideas for thinking routines for any content area and number sense routines for math.

5. Consider self-paced learning

In some classes, there might be a diverse difference in how quickly students can move through material. In this post “How to Create a Self Paced Classroom” from Cult of Pedagogy, you can read about the Modern Classrooms Project which might be a great fit if you really do need students to master many pieces of curriculum in a certain sequence. This will allow you to support the students going slower, build in some opportunities for peer coaching, and allow you to still cover the curriculum in the sequence you desire.

6. Use themes for unit planning

Use a throughline for a unit to allow all students to participate even if the work they are doing is different. This allows you to find materials for different levels of readers or provide guidelines that allow everyone to meet the end goal even though those end products may look different.

For example:

- Everyone is reading fantasy, just different books at different levels of text

- Everyone is learning about explorers but focusing on different ones

- Everyone is discussing “change” in response to their appropriate task

- Everyone is writing poetry and considering what poetry is but topics vary

- Everyone is writing a research paper but has a choice of a few topics

- Everyone is creating a project that answers the same guiding question

- Everyone has the same set of required pieces to do but there are multiple extensions

7. Plan multiple content areas holistically; search for cross curricular connections

If you teach elementary, consider how you can lessen your planning workload by overlapping content areas. You can arrange your curriculum in a way that looks for connections and cross over.

If you teach secondary, perhaps you can buddy up with a teacher that has the same students as you teach. You can both work on a project teaching different aspects. For example, a math teacher could work on fractions by having students change a recipe that feeds 4 people to multiplying it to feed the class of 24. Then, an English teacher could have them write directions for the recipe and a meaningful poem or memoir that explains why that recipe is important to their family or culture.

Here are some other ways you could make connections between curriculums that help everyone feel a part of the learning experience. For example, students might:

- read science books as a station in language arts

- write a script for a video teaching about economics in writing

- practice writing “how to” style directions in science class for growing plants

- create symmetrical shapes in art class to reinforce geometry

Often, this practice helps to solidify concepts for students because a fact or concept is not taught in isolation. I teach elementary and most of the specialists in my school actually love connecting to the content in class and appreciate knowing what I’m doing. This also reinforces the idea that school is helpful in the real world where “math” is not a separate activity of life. It is a part of measuring temperature, estimating where to put my dresser and bed in the bedroom, buying groceries, making a budget for my future dreams, etc.

There are many ways to adjust to meet the needs of students. Choose one of these ideas that you’d like to try and start there! No one is doing all of these things all of the time, but every teacher can make mindful choices to meet the needs of their students.

Start with what your students need and then take a step where their needs are leading you.

Amy Stohs

2nd Grade

Sign up to get new Truth for Teachers articles in your inbox

OR

Join our

community

of educators

If you are a teacher who is interested in contributing to the Truth for Teachers website, please click here for more information.

Discussion